At this stage of life, I have more time and space to reflect on the fragility and inequities of life. When I hit the trail for a hike or catch a glimpse of the jagged edges of Camelback Mountain, I sometimes ponder the plights of less fortunate men and less developed versions of the man I’ve become.

Recently, without notice, a Sonoran time machine swooped down and transported me from the desert. Back to south suburban St. Louis and my blue-denim-bell-bottom memories. Jerry and Joey (not their real names) lived near me on the same cul-de-sac street and the Oh Very Young prognostications of Cat Stevens looped through my brain.

Oh very young, what will you leave us this time?

You’re only dancin’ on this earth for a short while …

It was a weekend morning in the spring of 1974. I sat at the kitchen table, finishing up my last few bites of scrambled eggs and toast. My over-worked and under-appreciated mother washed the breakfast dishes. Over one shoulder, she blurted a provocative and unexpected question in my direction: “Mark, did you know Jerry is a practicing homosexual?”

Like most teens, I was bound up with insecurity. If I’d been less repressed, more freewheeling—or at sixteen had an ounce of awareness or comfort with my budding gayness—the idea of “practice” sex with an older boy down the street would have intrigued me. But at that moment I had no clue how to respond to my mother’s audacious question. I just shrugged my shoulders and muttered something like “Yeah, I think I’ve heard he might be.”

It didn’t occur to me that she might be fishing to learn about my sexuality. I just knew Jerry’s mother had died when he was young and his father, brothers and sisters had been left to make sense of her early exit. Whenever I walked by the front of their home, I saw the heaviness of their hearts had caused the foundation and the trees around it to sag.

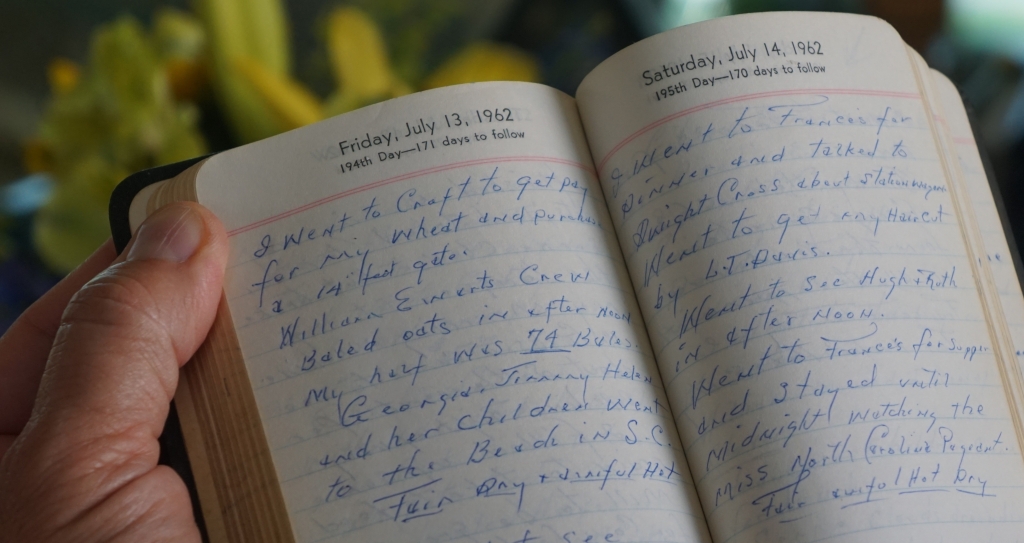

I’ve written a lot about my mother. She was smart, resilient and courageous. Many years later, she left me with her legacy of wise letters. But back in the 1970s, we weren’t approaching that. We were nearly three decades away from the profound sense of respect and understanding we would construct during her eighties and I would witness the love and deep regard she felt for my future husband and me.

Anyway, in the 1970s I was a withdrawn teen and she hadn’t yet sharpened her sensitivity. More specifically, like most parents then (and sadly many now), the implications of homosexuality and the image of two men engaged in mutually satisfying love frightened her. The word homosexual cast a shadow of shame, discomfort, darkness and isolation. Of course, without knowing it, I was absorbing the uninformed views about gay people coming through all sorts of channels–parents and neighbors, aunts and uncles, classmates and coaches, media and popular culture, etc.

I will never forget that trauma. Pushed and bullied down middle school hallways. Labeled a faggot for wearing my favorite purple sweater vest, a gift from my mother. As you might surmise, I learned it was best not to wear purple or pink or challenge society’s narrow mold of masculinity in the 1970s. It would take decades for me to love myself and create an unapologetic life as a gay man comfortable in pastels.

This is a prelude to tell you that, in addition to my personal sexual identity struggles, I felt sad and angry hearing and seeing Jerry and other young gay men ostracized for their nature, mannerisms and social awkwardness.

I don’t know where Jerry lives or anything about his adult life in 2019. But I now realize Jerry was a trailblazer. I owe a lot to the Jerrys of that time. Despite neighborhood chatter and suspicions, they were courageous enough to risk ridicule. To be true to themselves in the 1970s.

***

The story of Joey has nothing to do with societal pressures, sexuality or suburban mores. It’s a cataclysmic tragedy.

Joey was the blonde boy who lived next door. We were the same age. As youngsters, from kindergarten through fifth grade we waited for the same bus at the end of our street. He loved to roughhouse with his golden retriever when he came home from school. In sixth grade—lunch boxes in hand—we walked together to a new elementary school, built to handle the overflow of Baby Boomers.

Throughout the 1960s, once school ended in June, Joey and I raced to the top of the street with our neighborhood crew to play baseball in a vacant cemetery lot. We stayed there until our mothers or fathers stood on their front porches, cupped their hands to their mouths, and called our names for dinner.

In high school, Joey and I went our separate ways. I didn’t feel our connection any more. He was a mechanical guy. I wasn’t. I had a knack for stringing words together. He didn’t. He loved tinkering under cars. I loved singing on stage. While he developed a passion for playing the drums, my interest in the clarinet waned. In August of 1975, we continued down divergent paths. We left home for college at different Missouri schools.

Through it all, I felt no physical attraction for Joey, but I envied his apparently idyllic Please-Don’t-Eat-the-Daisies family life. Complete with the faux-wood-paneled Country Squire station wagon parked in their driveway, which I watched them load annually for summer vacations. Joey’s family seemed to embody the ideal of suburban happiness: two friendly and well-liked parents, two popular daughters who went on to become cheerleaders, two masculine and mechanically-inclined sons.

On a horrific Saturday in May 1976, everything changed. I came home from my seasonal job as a roller coaster operator at Six Flags and found my mother sobbing on the living room couch. She told me Joey had been killed in an accident. He was riding shotgun without a seat belt on the way home from his first year at college when the car he was in collided with another vehicle.

Spring flowers were blooming outside that day, but inside I was numb and devastated like everyone on our block. One cruel moment had ended Joey’s life and transformed his family’s home from the center of happiness into the epicenter of grief.

A few days later my mother, father, sister and I attended Joey’s wake. I didn’t know what to say to his bereaved father and mother. But I summoned a few inadequate words and gripped their brittle arms as we passed a pair of drum mallets stretched across Joey’s closed casket. It was frightening evidence of teenage mortality.

In 1980, I moved to the Chicago area. Whenever I returned to St. Louis to visit my parents and boyhood home, I thought of Joey and his family. Scampering in their yard with their dog as they prepared to load up their station wagon for the next trip. When Joey died, that era ended. Soon after, the rest of the family moved away.

Forty years have come and gone. Joey is on my mind again. Perhaps because he didn’t live long enough to pursue the next path at the base of rugged buttes. His Oh Very Young life ended back in the rolling Missouri hills without any chance to explore the west or have a spouse to share it.

Somehow, through good fortune, I’ve lapped his lifespan more than three times. After surviving a heart attack on my sixtieth birthday, I’m rounding the bend on the fourth lap here in Arizona.

For all the Jerrys and Joeys who have come and gone, I must keep telling my stories. I must make the most of the extra time I’ve been granted.

Oh very young, what will you leave us this time?