Even in this moment, you emerge undeterred,

answering absence, beckoning brilliance,

gathering gladness, harvesting happiness,

promising petals, savoring sunlight,

transforming trauma, welcoming wonder.

Even in this moment, you emerge undeterred,

answering absence, beckoning brilliance,

gathering gladness, harvesting happiness,

promising petals, savoring sunlight,

transforming trauma, welcoming wonder.

In 2008, in the midst of the Great Recession and the subprime mortgage crisis, I found myself reading the handwriting on the wall. My sister Diane and I were seated beside our mother. She had begun to slip mentally.

A physician at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago began to examine Mom to determine the severity of her cognitive impairment. As he proceeded to ask questions, I felt a sense of sadness and impending doom wash over me. I knew we were about to cross the threshold into a personal crisis for our family.

The doctor began. “Helen, tell me about yourself.”

She responded. “I was a child of the Great Depression.”

Those were my eighty-five-year-old mother’s first eight wise-and-weary words. I wasn’t surprised by her commencement. As her mental acuity waned and her short-term memory deteriorated, Helen always described herself as she existed near the beginning of her story.

She was proud to share her hard-working narrative. To explain how her father and mother–people of simple means and honest ambitions– somehow always found ways to put food on the table in the 1930s after the stock market crashed and some folks, overcome by their losses, jumped out of high-rise windows.

But Helen and her family survived the depths of the Great Depression in rural North Carolina. The experience forever shaped the woman she would become. She wore it as a badge of honor. Saving for a rainy day. Taking the surest path. Honing her skills. Consolidating the contents of half-empty ketchup bottles. Pulling the little red wagon up and down the hill to get groceries when the car went kaput and Dad’s heart weakened.

Building a career in Human Resources that often included working on Saturdays. Helping find government jobs for those who were disabled. Chatting about her love of gardening over the fence with neighbors. Trusting in time and patience. Squirreling away money. Parlaying it into smart investments. Turning a little into something that might someday become a lot.

***

Helen wasn’t alone. Her feelings and experiences represented those of an entire generation of Americans. Decades before she and other hearty souls like her–men and women who would also suffer one day from macular degeneration, heart disease, dementia, and more maladies–fought World War II, bought war bonds, rationed meals, moved to the suburbs to live in brick starter homes, lived the American dream, and produced a generation of Baby Boomers.

Helen passed away in 2013. There have been moments over the past few weeks when I’ve been grateful that she’s gone … not wanting her to experience the pain of this global pandemic that is consuming us, swirling over and through us, occupying every waking and nightmare-inducing moment of our lives. In other words, I’ve been thinking about Helen’s plight from nearly a century ago and that of the young children of today.

How will the fear and anxiety spawned by this pandemic shape their lives? How will it inform their values? How will it determine the choices they make? How will it influence their destinies? How will they describe themselves and define their lives when it becomes their turn to tell their stories to doctors in the year 2100?

Perhaps they will tell these kinds of stories.

***

My name is Anna. I was born on March 22, 2013. I was a child of the Global Pandemic. Before 2020, my mother and father owned and operated a popular restaurant in the Phoenix area. Customers raved about the great food and the lively atmosphere. But after the coronarivus entered our world, my parents were forced to abandon their business.

To survive, Mom ended up starting a business to deliver food to those who were house bound. Dad was handy. A few of the local condo communities hired him to handle day-to-day mechanical problems that came up. My parents didn’t earn much, but it was enough to sustain us in the short term.

I remember the tears and the anguish in our home. Everyone was afraid of contracting the virus. The news reports and the loss of life were devastating … especially to a few of my parents’ friends and restaurant acquaintances in major cities like New York, San Francisco and Chicago.

But Mom and Dad tried to remain strong. If anything, I loved them more during those years of hardship. For my seventh birthday, they insisted we would celebrate, though it felt as if all of us were living under a dark cloud … even here in the Valley of the Sun.

Mom and Dad always referred to me as their little princess … Princess Anna. So, Mom bought a banner with silver curls that seemed to float down from the sky. It was emblazoned with the word “princess” on it … and the three of us sat under a green metal canopy in a park in Scottsdale. They sang Happy Birthday to me and we enjoyed cake and ice cream outside. It felt like the safest place we could be at that time.

That’s a moment in my life I’ll never forget, because it happened at the beginning of all this uncertainty in the world … schools and businesses closing, the stock market bobbing and weaving, an over-worked and broken health care system fully taxed, our political system in disarray, our infrastructure crumbling. It was frightening for everyone, but most of us survived and became stronger.

The next few years were lean ones. But, with time, the economy grew strong again. People put their lives back together. Many years later, I ended up pursuing a career in health care, because I could see how desperate the world was for qualified doctors.

I never imagined I would become an epidemiologist. But it happened. Who knows what my life might have become if the health challenges of our world hadn’t become so apparent to me in 2020?

After all, I was a child of the Global Pandemic.

I never want to be that guy. The bore who tells the same stories at a party. The one you can’t escape in the corner of the room when all you want to do is wipe that silly-and-smug smile off his face. More specifically, the writer who drones on about subjects that don’t matter to anyone but himself.

I certainly wonder from time to time if the things I have to say are truly meaningful to others. If my synchronistic, slice-of-life stories and observations about universal subjects like family, fatherhood, friendship and flowers–not to mention love, loss, and late-in-life dreams and adventures–are fresh enough for followers or those who happen to read one of my books or stumble upon this page.

I’m not sure this classifies as a fear. But at the very least I have my creative doubts and vulnerabilities. I imagine it’s a condition other writers experience. Particularly when they’ve been diligently honing their craft for a while (i.e., written and published three books and nearly two years of bi-weekly blog posts) and strive to remain relevant in a culture that too often tweets and discards people, their ideas and historical perspectives more quickly than a wrapper around a fast-food sandwich.

Who knew this entire thread of creative questioning would be stimulated by a hike this morning in Papago Park? Where Tom and I amassed ten-thousand steps by eleven o’clock and a “No Drone Zone” sign caught my eye before today’s round of alliteration and wordplay could begin to take flight.

It was all the confirmation I needed. That remote-controlled, pilot-less aircraft or missiles are prohibited in this quiet corner of Phoenix (home to the nearby Desert Botanical Garden and Phoenix Zoo), where rugged buttes are patrolled by bighorn sheep.

That every book or post that bears my name is prepared with love, authenticity and good intentions.

That I’m doing my best to honor the meaningful and meaningless moments here in the “No Drone Zone” of my post-Midwestern life.

Retreat from impending pandemics, pundit prognostications and presidential prattle. Play in the garden. Greet the grace of nature. Gaze at gliding coyotes and giant cardons. Grant Sunday succulents a proper home. Gather and savor southern-facing light. Stand tall and shine in the darkness. Apply aloe. Ease the pain. March on.

Rare rain falls and pings against carport roofs. Such a solar sabbatical allows time for sun worshipers to pause and reflect on echoes ordinarily unheard.

Nature’s water droplets are like Cosanti bronze windbells. No two are identical. They hang and wave in the air at the whim of the wind.

Chiseled workmen clad in protective suits, gloves, helmets and visors pour 2,200-degree molten metal into sand-shaped molds in Paradise Valley.

A day later, they will extract cooled chimes handcrafted in burnished and patina finishes. The heat will forge the artistry. The wind will do the rest.

Eventually the melodious bells will leave the foundry, carefully wrapped in designed boxes for unknown destinations out of their control.

Some will ring in desert breezes on sun-scorched, palatial-or-postage-stamp patios in optimistic Arizona towns like Gold Canyon or Fountain Hills.

Others will fly with snowbirds to reign and ring above concrete back porches or cedar decks in harsher climates where snow collects on spruce tree limbs.

All of them will deliver unintended, unbridled and unfiltered messages. Raining here and ringing there for all to hear who are aware.

We live a block from this blaze of yellow and orange. It’s really not a field. It’s a swatch of a neighbor’s front yard filled with wildflowers that thrive on February opportunities, which the Valley of the Sun affords.

One of the things I’ve learned since leaving corporate life six years ago is that capturing images of nature lights my creative fire. Doing so, reminds me of the field of possibilities that await in life. Even for a guy who’s sixty-two.

Perhaps especially for a guy who’s sixty-two, because I still have a lot of observations to share. Things I need to say about my world, my nation, my state, my community, my family, my marriage, my individuality. Ideas I need to extract and plant out of my brain, water and nurture … just so I can give them light and see them appear and bloom on a page.

The fascinating part of the creative process is that when I sat down in front of my laptop this morning I had no clue what I would write about. But then I saw this photo on my phone and it spoke to me. In some way, the larger message I heard was “Keep writing, Mark. Write about what you know. What you observe. What you feel. What you dream of and worry about.”

So that’s what I do. A little every day. Sometimes I share it here. Other times I put it in a file with notes of other raw or unrefined observations that quickly blossom and fade in the desert sun.

But it’s the field of possibilities that continue to be my source of motivation. That prompt me to push ahead with my collection of true Arizona stories and desert fantasies, which I hope to publish in the next year. That connect me to a few fabulous followers who come here to read what I have to say.

I’ll keep doing it as long as I feel that impulse.

What happened to that wondrous world and the copper torch held high?

Where is the civilization our forefathers and magnificent mothers built?

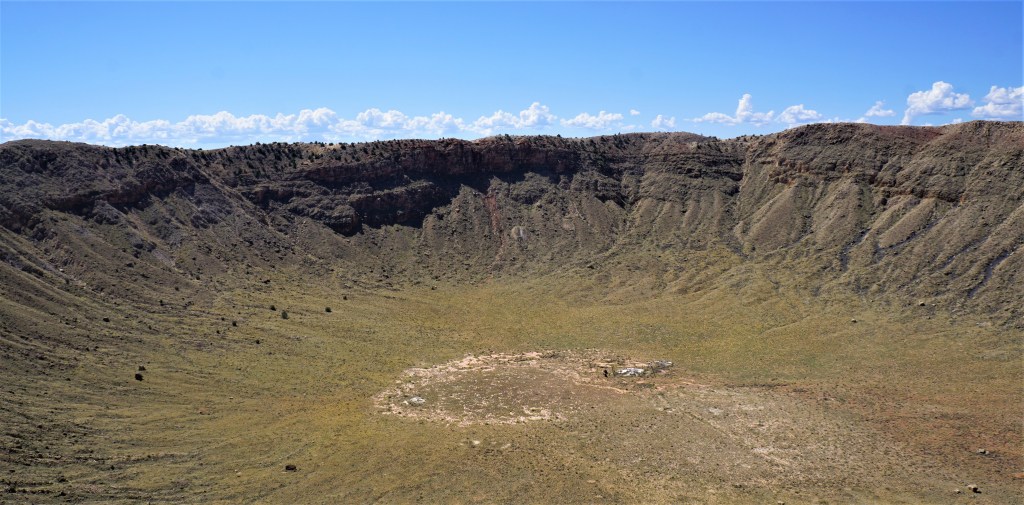

How was it hollowed out by a misguided meteorite that split the earth?

Why was it carved and quartered for the sake of few and ache of many?

When did it become an unbearable black hole they couldn’t climb out of?

Who forged this false universe and transformed it into a grim reality?

I guess we’ll never know … I guess we’ll never learn.

Written by Mark Johnson, February 7, 2020

I am forever a father. A son too, though the earthly connections to my parents ended seven years ago. Still, I choose to embed the themes of both father and son dynamics in my writing. I believe those roles and identities are rich with possibilities and pitfalls. They remind us of our past, our present, our place in the world.

Knowing my thematic propensities, recently Tom gave me a thoughtful, funny book that explores both sides of the equation. I’ll confess Michael Chabon’s stories Pops: Fatherhood in Pieces captivated me from the start–chronicling the escapades with his style-conscious, adolescent son Abe on their Paris Men’s Fashion Week odyssey–until the end when we learn of Pops, the doctor, and the author’s observations of his dad. That left me in tears.

It reminded me of my own father, Walter. How he coaxed me to tag along in 1962 when he got his hair cut. I was his number one son. At least that’s the way he introduced me to waiting patrons at the cosmetology college. Each time we went I feared Walter would force me to agree to a buzz cut from a boisterous barber, who snapped his cape like a matador and plucked black combs from tall jars of blue disinfectant.

I went along with Dad’s scheme anyway. I cowered behind his high-waisted, pleated pants before he stepped up into a swiveling chair for a cheap trim, a quick shave, and a dose of baseball banter between square-headed men wearing starched white shirts and boxy black-framed glasses.

In reality, I was Walter’s only son–four-year-old Bosco. It was an endearment he bestowed upon me, because I painstakingly pumped and stirred chocolate syrup of the same name into tall glasses of cold milk. In exchange, I sat in awe of my gregarious father as he gulped his coffee and savored his soggy Shredded Wheat. We loved each other, our playfulness, and kitchen table excesses.

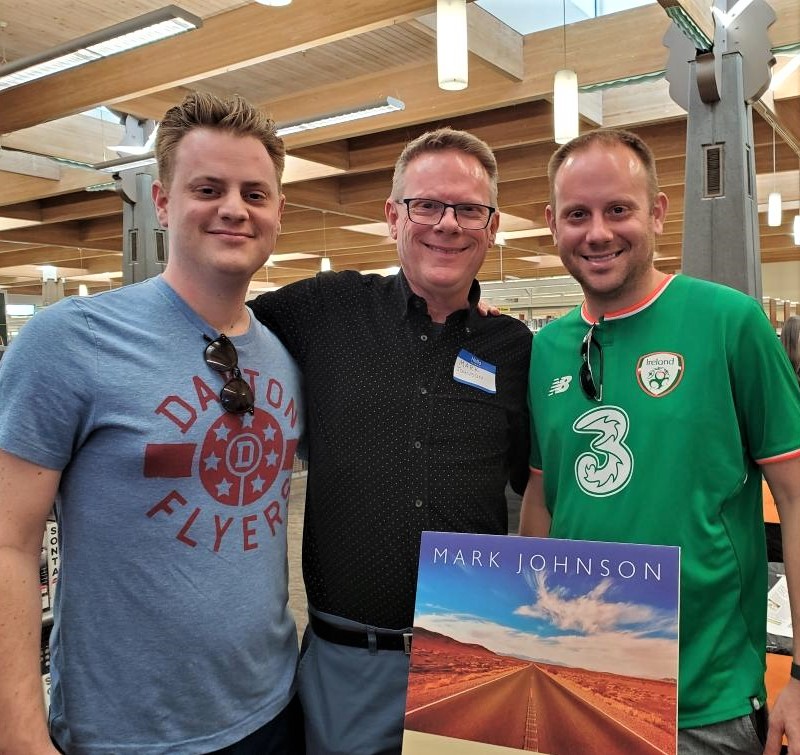

Though Walter has been gone for more than twenty six years, I was thinking of him as I finished reading Michael Chabon’s book last weekend. Then, in the same two-day period, along came a fresh chapter of my own fatherhood. Both of my sons, Kirk from Chicago and Nick from Tempe, came to support me on Saturday in my literary life at the 7th Annual Local Author book sale in Scottsdale.

Behind the scenes, they’ve been there since 2014 when I waved goodbye to corporate life. Rooting me on to explore this late-in-life literary fantasy that has become a reality. But Saturday was different.

I stood before Tom. First he took my photo in front of my table. Behind my three books. Later when Kirk and Nick arrived, I stood between my two adult sons. I remembered how far we’ve come since February 1992 … when my own fatherhood felt it had shattered in pieces … when their mother and I told them we were divorcing. I was moving into a new home. They would spend half of their lives with each of us.

Fortunately, in 1992 I had the gumption to stay in their lives and love them. We built a life together. Then Tom came along in 1996 and, over time, they learned to love him too. Together we stood by Kirk and Nick as they grew.

And then, suddenly on Saturday, they were standing by me.

It was nearly midnight on January 24, 1984, when I held him for the first time at Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Illinois. My son, Nick, had just been born on a bitterly cold night in Chicago’s northwest suburbs.

His mother and I fell in love with him at first sight. His peaceful expression after a difficult labor. His tiny fingers and toes. His shock of dark hair that would soon turn blonde. I adored every bit of my firstborn son.

Today, on Nick’s thirty-sixth birthday, a lifetime of firsts are flooding my brain. Perhaps it’s because I know how far we’ve come in three and a half decades. Climbing the winding ramp to the upper deck at Wrigley Field. Watching him kick a soccer ball at two and, at five, size up his little brother Kirk when he came home from the same hospital. Marveling as Nick drained clutch three-pointers on the basketball court.

In later years, Nick and I endured more complicated chapters. Finding our way together after his mom and I divorced. Telling him I was gay. Introducing Tom to him and Kirk. Seeing the four of us bond over a comedic basset hound. Surviving testy teenage years. Driving Nick to the University of Iowa for his freshman year.

More recently, I’ve gotten to see Nick stand by Tom and me on our wedding day, say goodbye to his grandmother, sort through his career options, follow his dream and pursue a new life in Arizona, find crutches when he tore up his knee in 2017 (two months after I suffered a heart attack), campaign for a democratic senator in Arizona, and pick grapefruits, oranges and lemons from our condo trees this January.

In 1984, I never imagined any of these chapters … any of these firsts. Or that Nick and I would each leave Illinois and end up living ten miles from each other in the Arizona desert. But that’s where our lives have led to this point … far from the arctic cold of northern Illinois.

This morning, as Tom and I drove home after our gentle yoga class, I called Nick to wish him a happy birthday. I could hear happiness in his voice. He was out for a long walk on a beautiful day in the Valley of the Sun.

A beautiful day, indeed. Nick is my son.

Arizona’s Crosscut Canal connects Scottsdale, Tempe and Phoenix. Depending on the day and the immediate weather, it can carry a trickle of water or channel a deluge of monsoon storm drainage into a network of other canals that irrigate surrounding communities in the Valley of the Sun.

One stretch of the canal winds between Camelback Mountain on the north and the east-west artery of Indian School Road on the south. It’s just steps from the office of Omni Dermatology where, since December 9, I’ve been meeting Amanda (and Claudia, her holiday replacement) three times a week for superficial radiotherapy treatments to bombard the invasive squamous cancer cells on my left hand.

Today was treatment nineteen. I’ll be happy to see it end Thursday morning with session twenty. Certainly, I was ecstatic to hear Dr. R tell me yesterday that my hand has healed beautifully. Still, I’ll admit a strange sense of sadness is creeping into my soul. That’s because I will no longer share stories and perspectives with Amanda.

During each session, we’ve chatted as she applied gel to the back of my hand, rolled a detection device across my skin to monitor the regeneration of healthy cells, taped a square of metal with a hole in the middle over the suspicious spot, placed the blue flak jacket, matching collar and protective goggles on me, and lowered the radiotherapy “gun” until it was secured against my skin.

In the grand scheme of things, perhaps Amanda’s stories were designed initially to distract me from the real reason I was there, the real anxieties I felt at the end of last year. But, over time, we’ve gotten to know each other intimately.

For instance, we’ve engaged in conversations about her son’s ski team excursions to northern Arizona, the identifying southern lilt in her voice that came from her Georgia roots, her part-time job as a real estate agent, my passion for writing and staying relevant in my sixties, and her hope to celebrate her approaching fortieth birthday in Hawaii with her husband. Just today, she told me she purchased my first book From Fertile Ground and was excited to read it.

Shortly after her book-buying revelation, Amanda excused herself for a minute. She left the room. Left me to my devices. Hit the radiotherapy switch. Then, forty-five seconds later–after the quiet hum of the machinery had ended–she reentered the room.

“Just one more measly treatment,” I muttered as she gathered my protective gear.

“It’s so funny you would say that,” Amanda laughed. “Measley, with an additional “e”, was my maiden name.”

At this juncture, I realized the connections before me. The mystical and idiosyncratic language of our lives. The canals in the desert. The tributaries that run through our human interactions without us really ever understanding how and why.

I felt the same synchronicity in St. Louis on July 6, 2017. That’s when Jacob, an EKG technician at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, ran a device and cool gel across my chest. As he performed his duties to determine the magnitude of the obstruction on the left side of my heart, I felt safe in Jacob’s hands. Evidently, he felt secure too, because in the following thirty minutes that day he shared his life story with me … that of a new father protecting his infant son and trying to adjust to a sleep-deprived schedule.

Perhaps because I’m more aware of my mortality in my sixties, I’m predisposed to pondering these present moments … what it felt like to connect with Jacob with my life hanging in the balance … what it will feel like to meet Amanda for just one more “measly” or “Measley” superficial radiotherapy session.

No matter the reason for my acute awareness, I’m ready to put this cancer scare behind me. I’m grateful for what lies ahead along the canal that trails through my desert life.